From Beethoven's Rod to AR Glasses: The Long, Quiet Revolution of Open-Ear Audio

Update on Oct. 19, 2025, 1:01 p.m.

To the modern consumer, open-ear audio seems like a recent innovation, a clever new gadget for runners and cyclists. But this technology is no overnight success. Its journey didn’t begin in a Silicon Valley startup, but nearly two centuries ago, with a deaf composer desperately trying to hear his own masterpieces. The story of open-ear audio is a long, quiet revolution, a technology that spent decades whispering in the corridors of medicine and the battlefields of war before it was ready to speak to the mass market.

This is the story of how a fundamental principle of physics evolved from a curious medical device into a billion-dollar consumer electronics category, and why its most exciting chapter is still to come. It’s a tale of two competing technologies, a market that suddenly split in two, and a future where the very concept of a “headphone” might just disappear.

Act I: Whispers Through Bone (1800s - 2000s)

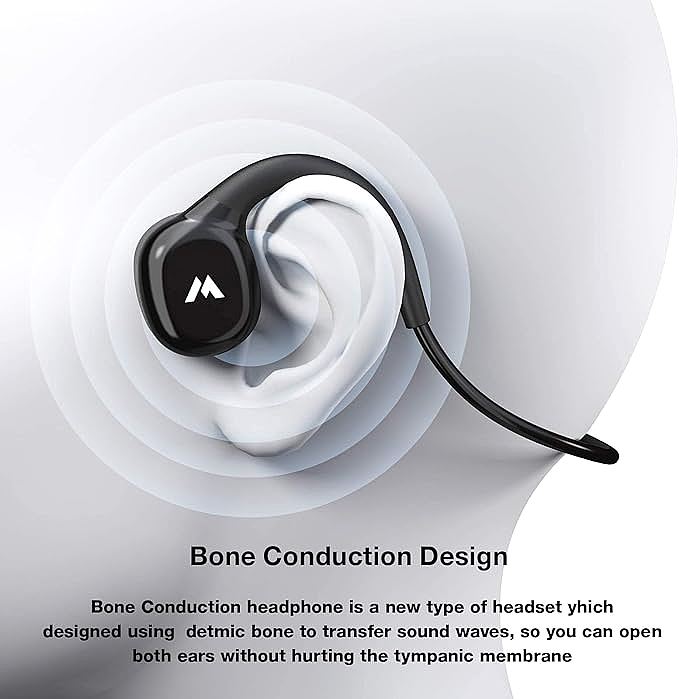

The foundational concept of bone conduction—transmitting sound through vibration—has been understood for centuries, most famously by Ludwig van Beethoven and his rod. But it wasn’t until the age of electronics that it could be weaponized. In the 1920s, inventor Hugo Gernsback patented the “Osophone,” a device that used bone conduction to aid the hearing-impaired, marking one of the first transitions from principle to product.

For the next 80 years, however, the technology remained firmly in the realm of niche, professional applications. Its development was driven not by consumer demand, but by extreme necessity. The military saw its potential for high-noise environments, developing throat mics and bone conduction headsets that allowed tank commanders and special forces operators to communicate clearly over the roar of engines and explosions. Audiologists refined it for medical testing. It was a powerful, proven, and rugged technology, but it was also expensive, clunky, and sonically limited. For the average music lover, the rich, high-fidelity world of air conduction headphones was infinitely more appealing. Bone conduction was a tool, not a toy.

Act II: The Market Awakens and Diverges (2010s - Present)

The catalyst for change arrived not as a single breakthrough, but as a perfect storm of converging trends in the early 2010s. The maturation of Bluetooth technology finally cut the cord, making wearable audio practical. Advances in waterproofing (IP ratings) made electronics durable enough for outdoor use. And most importantly, a global wellness boom created a massive new market: millions of runners, cyclists, and fitness enthusiasts who wanted a soundtrack for their activities but couldn’t afford the dangerous isolation of traditional earbuds.

Into this storm stepped a company called AfterShokz (now Shokz). They didn’t invent bone conduction, but they relentlessly perfected it for a consumer audience. They miniaturized the transducers, lightened the frames, and focused on a single, killer use case: situational awareness for athletes. Their success was meteoric, and for a time, “bone conduction” and “Shokz” were synonymous.

But as the market grew, it began to fracture. A great divide appeared, splitting the open-ear world into two distinct philosophical and technological camps.

Path 1: The Technology Purists. Led by Shokz, this camp is dedicated to “true” bone conduction. They invest heavily in patented transducer technology to deliver the most efficient vibration with the least amount of leakage. Their products are aimed at a premium market of serious athletes and professionals who demand the best possible performance and are willing to pay for it.

Path 2: The Experience Pragmatists. This camp recognized that for many users, the goal wasn’t technological purity, but simply the experience of open-ear listening at an affordable price. This led to the rise of directional audio. Tech giants like Bose (with their Frames sunglasses) and Amazon (Echo Frames) poured R&D into creating miniature, highly focused speakers that could create a private sound bubble without touching the ear. At the lower end of the market, brands like MOING used the same principle to create products like the BC-8. By leveraging mature, low-cost speaker technology, they could deliver the core benefit—situational awareness—for a fraction of the price of high-end bone conduction. They marketed it as “bone conduction” because the term was recognizable, but their success proved the market cared more about the “why” (I can hear my surroundings) than the “how.”

Act III: Echoes of the Future (2025 and Beyond)

The divergence of the market is not the end of the story; it’s the beginning of the next, far more interesting chapter. The ultimate destiny of open-ear audio is not to be a better headphone, but to become the default audio layer for the next generation of computing.

The first step is the transition from headphones to “hearables.” As seen in audio sunglasses, the technology is already detaching from the traditional headphone form factor. The next logical step is its integration into standard eyeglasses, helmets, and other head-worn apparel.

The true paradigm shift, however, will come with the rise of Augmented Reality (AR). For AR glasses to be socially acceptable and truly useful, they must overlay digital information onto the real world without isolating the user from it. Open-ear audio is the only technology that can deliver private, contextual audio notifications (“Turn left in 50 feet,” “Your colleague John is approaching”) without sealing the user off.

This will also usher in the era of Computational Audio. Future devices won’t just be passive speakers; they will be active listeners. Using arrays of microphones and powerful on-board AI, they will be able to understand the user’s acoustic environment. Imagine a device that can selectively dampen the drone of an air conditioner while amplifying the voice of the person you’re talking to, or translate a foreign language in real-time, overlaying the translation directly onto your auditory scene. This is the endgame: not just hearing your digital world, but having your device intelligently manage and enhance your perception of the real one.

Conclusion: The End of the Headphone as We Know It?

The journey from Beethoven’s rod to today’s crowded market has been a long one. What began as a single technology has now become a rich and diverse ecosystem of ideas. But the most profound change is yet to come. Open-ear audio is poised to break free from the “headphone” category altogether. It is becoming a foundational component of the augmented, computationally-enhanced future. Its ultimate goal is to become so seamless, so integrated, and so intelligent that we forget it’s there at all—the final step in a revolution that ends not with a bang, but with a perfectly integrated, invisible whisper.